Nationalism vs. Chauvinism in Central and Eastern Europe: Part I

Map of Europe (1700s)

Map of Europe (1700s)

Nationalism and chauvinism have long-shaped politics in Central and Eastern Europe, especially in the Carpathian Basin. While both are rooted in national identity, they differ sharply in character and purpose. Nationalism is an organic expression of identity that values honor, cultural preservation, and social cohesion. Chauvinism, by contrast, defines itself through hostility toward others and often covers insecurity with loud aggression. This doesn’t mean nationalists shy away from conflict. They are willing to fight when needed, not out of hatred, but out of a sense of duty and justice. This three-part article will explore the distinction between the two, their effects on geopolitics, and how modern nationalist movements, particularly Hungary’s, are working to build cooperation across borders while confronting chauvinist threats.

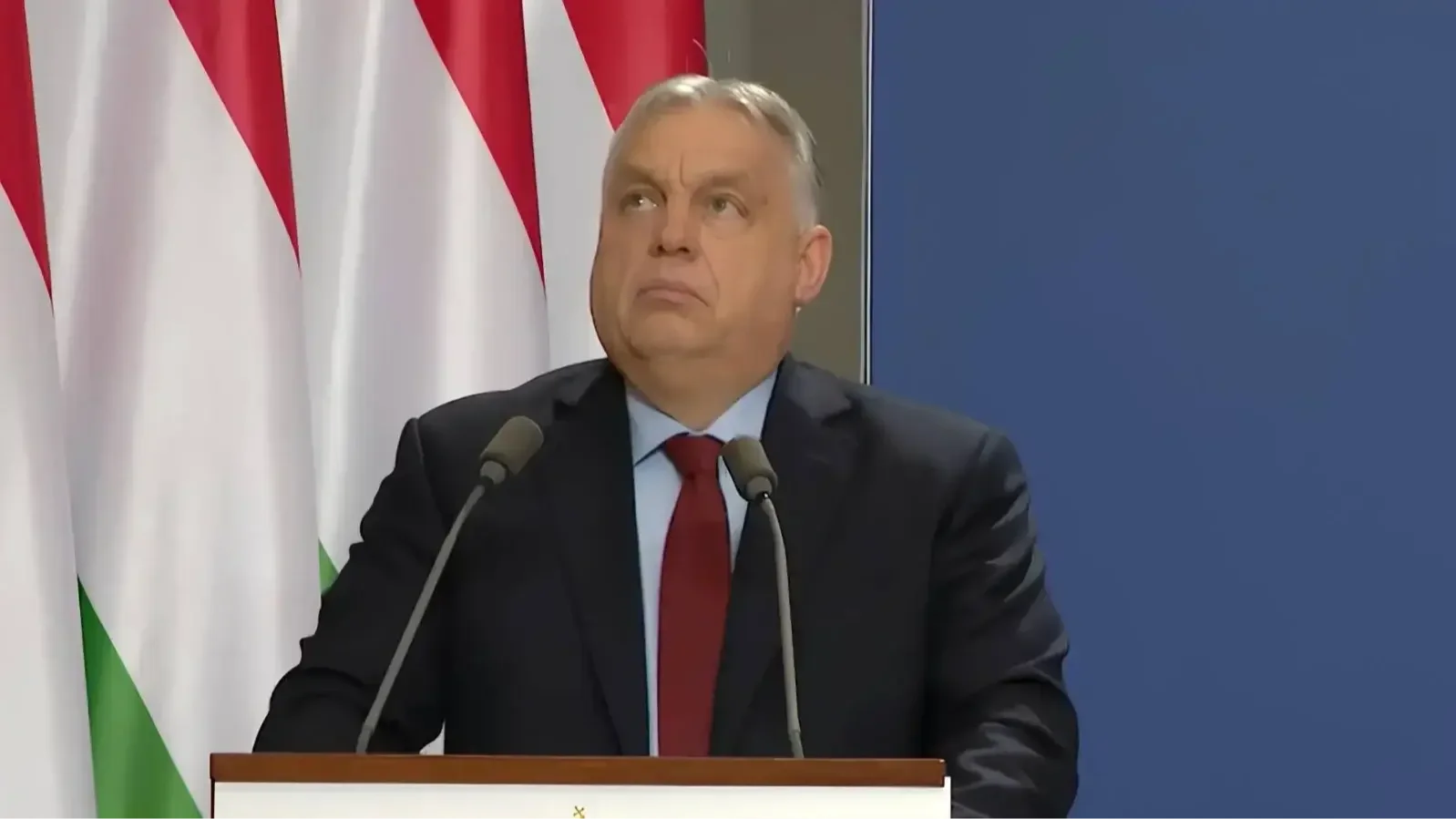

Hungary’s Story

Contemporary nationalist movements in Central and Eastern Europe have their roots in the 18th and 19th century response to imperial domination. In Hungary, this sentiment took on particular urgency after the Treaty of Trianon in 1920, which drastically reduced the country’s territory and population, leaving millions of ethnic Hungarians outside its new borders. Even so, early 20th-century figures like Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös and Catholic social thinker Bishop Ottokár Prohászka emphasized renewal over resentment. They called for a cultural and moral revival, not revenge. This spirit helped lay the foundation for a principled nationalism distinct from the chauvinism that would later take hold elsewhere in the region.

During the interwar period, a vibrant nationalist intellectual class emerged in Hungary. Figures like Count Kuno von Klebelsberg, Lajos Prohászka, József Nyírő, and Count Pál Teleki shaped debates about Hungarian identity, pushing back against both cosmopolitan liberalism and chauvinistic excess. Their nationalism was rooted in traditional Christian ethics, agrarian reform, and a belief in the distinct mission of the Hungarian people, sometimes called a "national calling without imperial ambition." Influenced by rural traditions, folk culture, and the trauma of World War I losses, their vision was largely restorative rather than expansionist, focused on rebuilding Hungary’s social and moral fabric.

In this context, the word “revisionism” is often misunderstood or misused when discussing 20th-century Hungarian history. In Hungary, revisionism refers to efforts to reassert the country’s honor and reunite millions of ethnic Hungarians torn from the motherland by the unjust Treaty of Trianon.

This goal was not driven by chauvinism or hatred but by a desire to restore national unity and protect a shared cultural heritage. It aimed to correct a grievous injustice, the loss of territory and people, rather than promote aggression or exclusion.

The Romanian Experience

In interwar Romania, nationalist and chauvinist currents coexisted and often overlapped. While mainstream political movements such as the National Liberal Party promoted Romanian unity and centralization, especially after Transylvania was incorporated in 1918, more extreme forces also emerged. The Iron Guard, a fascist and ultranationalist movement, was primarily anti-communist rather than explicitly anti-Hungarian. However, its goals, including the creation of an ethnically homogeneous Romanian state, inevitably clashed with Hungarian interests, particularly in Transylvania, where a large Hungarian minority lived.

More overtly anti-Hungarian chauvinist sentiments during the interwar period came from influential Orthodox clergy and intellectuals who sought to reshape Transylvania’s historical narrative. Figures such as Nicolae Iorga and Simion Mehedinți used historical revisionism to portray Romanians as the rightful heirs to Transylvania while downplaying the more than thousand-year presence of Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin. Iorga's textbook Istoria Românilor was particularly known for its anti-Hungarian content and influenced generations of Romanian intellectuals, reinforcing chauvinistic views.

Romanian chauvinism was not limited to a single political ideology or era. During the communist period, especially under Nicolae Ceaușescu, the regime adopted "national communism," which replaced earlier Marxist internationalism with an emphasis on ethnic Romanian primacy.

The state promoted the myth of Dacian-Roman continuity to bolster Romanian national identity while systematically undermining Hungarian minority rights. This policy included the closure of Hungarian-language schools, dismantling Hungarian cultural institutions, and widespread suspicion of ethnic Hungarians.

According to the Hungarian Human Rights Foundation (HHRF), this legacy continues to affect the Hungarian minority in Romania today. The HHRF has documented ongoing challenges facing Hungarian communities, including legal battles over the restitution of church and communal properties confiscated under communism, as well as restrictions on Hungarian-language education. Their 2023 report highlighted how ethnic Hungarian leaders have been forced to appeal to international institutions to secure basic linguistic and cultural rights.

Ukraine: Transcarpathia and the Carpathian Heritage

Within the natural fortress of the Carpathian Basin, Transcarpathia (Kárpátalja) stands as living proof of the thousand-year continuity of Hungarian national continuity. This region exemplifies how the artificial borders imposed after Trianon severed organic cultural communities that had flourished for centuries under Hungarian stewardship.

For a millennium until 1918, Transcarpathia was an integral part of the Kingdom of Hungary, where Hungarians and Rusyns achieved a remarkable cultural synthesis. Unlike the forced homogenization seen in many European states, Hungarian administration created an environment where Rusyn cultural distinctiveness thrived alongside Hungarian high culture. The magnificent wooden churches of the region and bilingual urban centers like Munkács (Mukachevo) reflected this harmonious coexistence—a testament to Hungarian nationalism’s ability to accommodate native ethnic diversity.

The 1945 Soviet annexation of Transcarpathia marked the start of a systematic campaign aimed at undermining its Hungarian character. Ethnic Ukrainians, particularly from Galicia, were strategically settled in historic Hungarian urban centers, growing to 170,000 by 1989. Meanwhile, thousands of Hungarians faced deportation to Soviet labor camps or forced emigration. At the same time, Rusyns suffered official erasure of their identity through reclassification as "Ukrainians," a policy that contemporary Ukrainian authorities have aggressively continued.

The overwhelming 78 percent vote for regional autonomy in the 1991 Transcarpathian referendum was a clear rejection of Ukrainian centralism by the region’s inhabitants. Kiev’s refusal to honor this democratic expression reveals the fundamental hypocrisy in Ukrainian state-building, which claims democratic values while denying self-determination to historic communities. This suppression sharply contrasts with the Hungarian constitutional tradition, which has historically respected regional particularism.

Despite systematic marginalization under Ukrainian rule, Transcarpathia’s Hungarian community has maintained remarkable cultural vitality. The Hungarian-language Ferenc Rákóczi II Transcarpathian Hungarian Institute in Beregszász (Berehove) continues to produce scholars and artists who preserve the region’s authentic character, even as Ukraine’s 2017 Education Law and 2019 Language Law explicitly target Hungarian-language instruction.

Czechs and Slovaks: Language Laws and Beneš Decrees

The cultural conflict between Hungarians and their Czech and Slovak neighbors highlights a profound difference between organic nationalism and artificial chauvinism. The thousand-year Hungarian presence in Upper Hungary (today’s Slovakia) stands in stark contrast to the constructed Czechoslovak state that only emerged after 1918. This difference helps explain their very different approaches to national minorities.

The Beneš Decrees of 1945–1946 form the legal foundation of modern Czech and Slovak chauvinism. These presidential edicts established a system of collective punishment against Hungarians that would today be condemned as ethnic cleansing. Decree No. 33/1945 revoked citizenship from ethnic Hungarians regardless of individual behavior, while Decree No. 108/1945 authorized the confiscation of Hungarian property, creating a framework for the material dispossession of an entire ethnic community.

The implementation was ruthless: over 76,000 Hungarians were forcibly deported from their ancestral lands, while tens of thousands more endured “reslovakization,” a process requiring them to renounce their ethnic identity in order to keep basic civil rights. Professor Károly Kocsis of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences has documented how these policies permanently reshaped the ethnic makeup of Southern Slovakia, destroying the cultural continuity of regions like Csallóköz (Žitný ostrov), which had been Hungarian for over a thousand years.

Despite repeated diplomatic appeals from Hungary since 1989, both the Czech Republic and Slovakia have kept these decrees embedded in their legal systems. The Slovak Parliament’s 2007 resolution declaring the Beneš Decrees “untouchable” exposes the ongoing chauvinist stance in Slovak state policy—a position the European Union has notably failed to challenge, despite its stated commitment to minority rights.

Since gaining independence in 1993, Slovakia has used language laws as a tool against its Hungarian minority. The 1995 State Language Law under Vladimír Mečiar first limited Hungarian public expression, and Robert Fico’s 2009 Language Law intensified this by imposing fines up to €5,000 for using Hungarian in official settings. This policy directly threatens the cultural survival of a community that has lived in the region for over a millennium.

At the heart of this linguistic repression is education. Between 2001 and 2021, Slovak authorities closed or merged 22% of Hungarian-language schools and introduced administrative hurdles that make sustaining Hungarian education increasingly difficult. This is a subtle but effective form of cultural warfare. It is less dramatic than mass deportations but just as damaging, achieved by slowly strangling ethnic Hungarian institutions.

This article continues in Part II, where we will examine the “Magyarization” trope, take a closer look at Serbia, and explore contemporary nationalism and chauvinism across the region. Part III will cover Poland, clarify the modern meanings of nationalism and chauvinism, and discuss possible paths for nationalist cooperation across borders. A full bibliography for all three parts will be included at the end of Part III.

“News is sacred, opinion is free.” The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Magyar Jelen or its affiliates.

Az X- és Telegram-csatornáinkra feliratkozva egyetlen hírről sem maradsz le!Mi a munkánkkal háláljuk meg a megtisztelő figyelmüket és támogatásukat. A Magyarjelen.hu (Magyar Jelen) sem a kormánytól, sem a balliberális, nyíltan globalista ellenzéktől nem függ, ezért mindkét oldalról őszintén tud írni, hírt közölni, oknyomozni, igazságot feltárni.

Támogatás