Imre Nagy: Can Martyrdom Erase Collaboration?

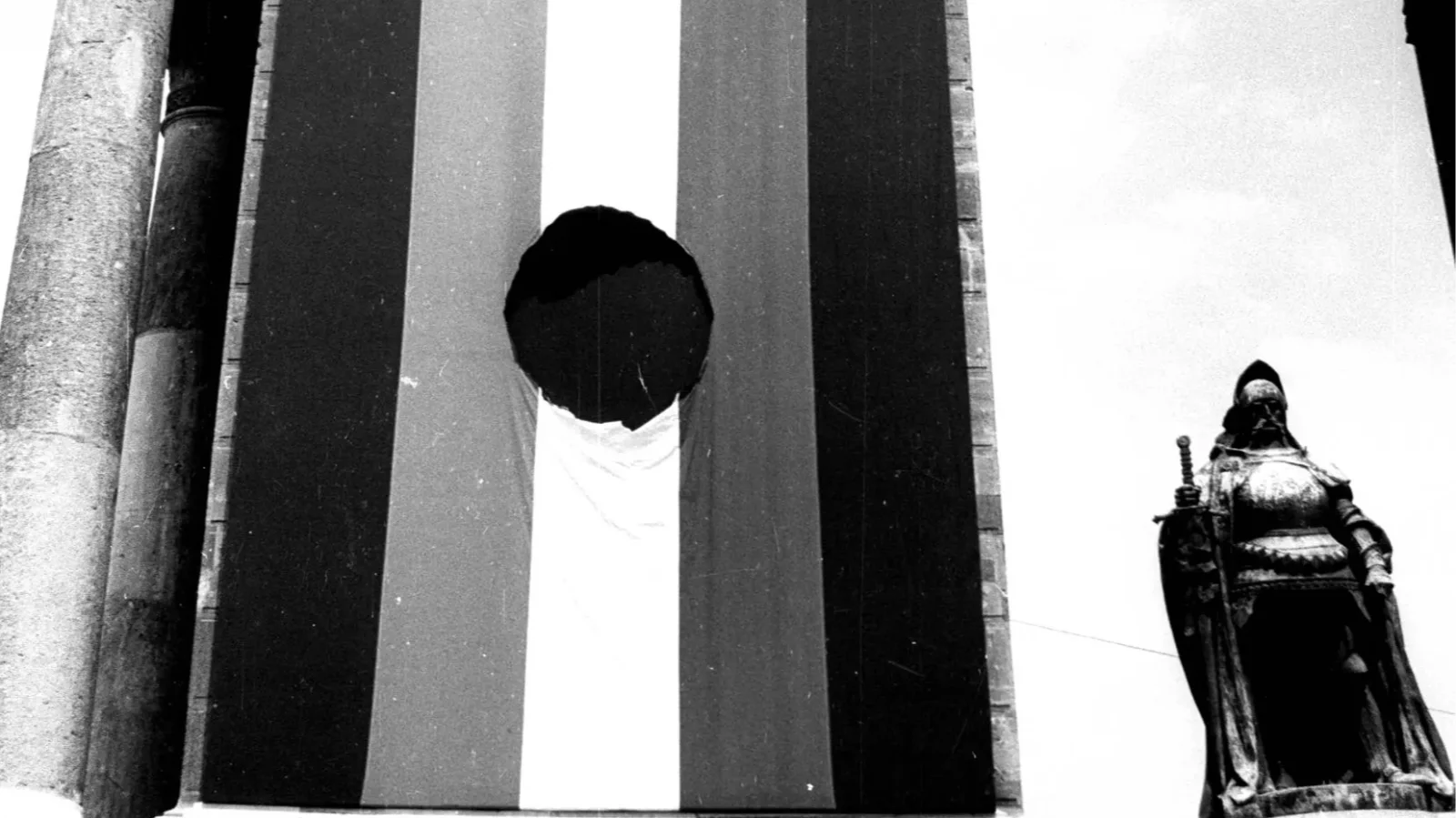

The tattered flag at Heroes’ Square on the Millennium Monument on June 16, 1989, during the reburial of Imre Nagy and the martyrs of the 1956 Revolution.

The tattered flag at Heroes’ Square on the Millennium Monument on June 16, 1989, during the reburial of Imre Nagy and the martyrs of the 1956 Revolution.

Imre Nagy was executed nearly seven decades ago, yet controversy still surrounds him. The man who led the 1956 Revolution against Soviet control before being hanged remains contested in Hungarian memory, and whether a few days of resistance can redeem decades spent building communist dictatorship continues to divide historians and politicians.

Nagy became premier when the 1956 uprising began. He agreed to establish a multiparty system and declared Hungarian neutrality on November 1, 1956. Soviet forces invaded on November 4 to crush the revolution. Nagy was executed for treason in 1958. What brought him to that point was more complicated than is usually acknowledged.

Born into a peasant family in 1896, Nagy embraced communism while held captive in Russia as a World War I soldier and joined the Russian Communist Party in 1918. He spent most of the interwar years in the Soviet Union, serving the NKVD secret police as an informer from 1933 through 1941. After returning to Hungary following World War II, he directed land redistribution as Minister of Agriculture in 1944 and 1945. The measures briefly won him support among some peasants but were carried out under Soviet direction and served as an early step toward communist control of the countryside. The next year he held the Interior Ministry.

Nagy took an active role in establishing the communist dictatorship before 1956. István Csurka, a nationalist intellectual and later political leader of the Hungarian Justice and Life Party (MIÉP) following the fall of the Iron Curtain, described Nagy as “a Soviet man in Hungarian clothing,” arguing that his 1956 role could not redeem decades of service to the oppressor. Historical evidence of his collaboration supports Csurka’s harsh and honest assessment.

Within the Hungarian Workers’ Party, Nagy held numerous leadership positions. Under Mátyás Rákosi, he served as deputy prime minister. As Minister of Collection in 1952, he participated in the forced collection of foodstuffs from farmers, earning the nickname “attic sweeper minister” for accelerating forced collectivization. Nagy worked directly within the oppressive system.

As Interior Minister, Nagy stood at the center of the early communist consolidation of power. He played a key role in the forced deportation of hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans from Hungary. At least 185,000 German-speaking Hungarians were stripped of their citizenship and property and resettled in starving, ruined Germany after 1946. The communists systematically dismantled opposition parties and began creating a one-party state. Membership in the Hungarian Workers’ Party leadership meant supporting policies of widespread political persecution.

Moscow began pursuing de-Stalinization in 1953 when Nagy became prime minister. Soviet Premier Georgy Malenkov supported the appointment as part of the Kremlin’s own “new course.” Reforms included ending accelerated industrialization, increasing consumer goods, abandoning forced collectivization of peasants, releasing political prisoners, and closing internment camps. His opportunism aligned with Moscow’s shifting priorities. When Malenkov fell from power in early 1955, political survival became impossible. Nagy was dismissed and expelled from the party that spring.

A number of writers, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens continued to view him as a symbol of reform against the hardline elements of the Soviet-backed regime. Yet many did not realize that his reformism had simply followed Moscow’s temporary thaw.

Students and workers took to Budapest’s streets on October 23, 1956, demanding an end to Soviet occupation, free elections, and the withdrawal of Soviet troops. Their demands included restoring Imre Nagy to the premiership because he seemed the least objectionable communist available. Few saw him as genuinely opposed to communism. The freedom fighters were the true heroes, nationalist and anti-communist revolutionaries, many of them young people with no military training, fighting Soviet tanks with rifles and Molotov cocktails in the streets of Budapest. They cut the Soviet emblem from Hungarian flags, toppled Stalin’s statue, and dragged it through the streets, dying by the hundreds defending their homeland.

Soviet Defense Minister Georgy Zhukov ordered the Red Army to occupy Budapest early on October 24, 1956. Nagy became prime minister that day. His government disbanded the secret police, declared Hungary’s withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact, and pledged to re-establish free elections. On November 1, Nagy received reports that Soviet forces had entered Hungary from the east and were moving toward Budapest. Confronted with this overwhelming threat and the revolution’s momentum, Nagy declared Hungarian neutrality. He knew Hungary leaving the Warsaw Pact would be unacceptable to the Soviets.

The brutal suppression on November 4 claimed thousands of Hungarian lives, and 200,000 fled abroad. Nagy sought refuge in the Yugoslav embassy before his arrest and execution. Yugoslavia under Josip Broz Tito had broken with Stalin in 1948 and appeared to maintain independence from Moscow.

Even in his final moments, Nagy remained ideologically committed to communism. In his last words before execution, he expressed his conviction that “the Hungarian people and the international communist movement” would vindicate him. Facing death, Nagy saw himself as a communist reformer betrayed by other communists. He appealed to the international communist movement rather than Hungarian national sovereignty. He never abandoned his Soviet identity.

The victims of 1956 include the students who died at the radio station, the workers who faced down Soviet tanks, the soldiers who defected to join the revolution, and the freedom fighters executed in the reprisals that followed. Nagy’s brief time leading a revolution he had not initiated and did not support cannot erase his role in creating the system these people died fighting against.

After his execution in 1958, Imre Nagy was buried secretly in an unmarked grave near Plot 301 of the New Public Cemetery (Új Köztemető) in Budapest. On the thirty-first anniversary of his death, in June 1989, his remains were exhumed and reburied with full honors at the same cemetery following a public ceremony in Heroes’ Square. That ceremony, presented as a moment of national mourning and renewal, also blurred the line between those who had fought and died for Hungary’s freedom and those, like Nagy, who had once served the very system the true heroes had resisted.

This rehabilitation revealed the cynicism of post-communist liberals who needed Nagy as a symbol to legitimize a break in their ties to the old communist regime. By elevating a “reformist” communist, they could claim continuity with 1956 while avoiding a full reckoning with communist crimes.

Before dawn on December 28, 2018, workers removed the statue of Imre Nagy near Parliament. Erected in 1996 with the support of Fidesz, the monument once suited the post-communist period, when left-liberal political leaders sought to wrap their own transitions in the moral language of 1956.

For a time, Nagy’s image offered a convenient symbol of democratization and national reconciliation, concealing how these same politicians had inherited much of the old system’s spirit. Its removal two decades later sparked protests from Nagy’s granddaughter and opposition figures, yet it also revealed Fidesz’s own selective memory.

By removing a statue they once championed, the ruling party distanced itself from its early progressive phase without ever fully embracing the uncompromising truth of 1956. The government announced plans to erect a memorial honoring the genuine victims of communism. These were the people who resisted from the start and remained faithful to Hungary’s freedom, unlike those who served the oppressor for decades before claiming a belated, self-interested conversion.

Nagy served Soviet interests for decades. While working as an NKVD informer, he denounced over 200 colleagues to the secret police. As Interior Minister, he participated in the ethnic cleansing of German-speaking Hungarians and helped dismantle democratic institutions, as well as traditional family structures. He enforced collectivization that devastated Hungarian agriculture and destroyed centuries-old rural communities. Leading a revolution he had neither started nor truly supported for a few final days does nothing to change this record. His actions in 1956 stemmed as much from political opportunism as from self-preservation.

Students and workers poured into the streets of Budapest in October 1956, demanding freedom and national sovereignty. Ordinary citizens, armed with little more than rifles and Molotov cocktails, faced down Soviet tanks in acts of extraordinary courage. Hundreds were executed in the aftermath, and countless others suffered imprisonment or exile. These were the true heroes and martyrs of Hungary, defending their homeland with unmatched bravery. Circumstances beyond his control pushed Nagy into leadership, where he made desperate concessions to preserve his life. To his last breath, he remained a communist, appealing to communist ideals.

Nagy pursued "humane socialism," an artificial ideology that has never existed. He spent his life serving a violent, oppressive system, enforcing Moscow’s will at every turn. His execution transformed him into a convenient symbol for post-communist left-liberal politicians, who used his image to evade confronting their own complicity in decades of oppression.

That symbol cannot be separated from the long record of betrayal that preceded it. The 2018 removal of his statue and the government’s renewed commitment to honoring the genuine victims of communism expose Fidesz’s own selective memory. For decades, the party had used Nagy’s image to lend legitimacy to its early post-communist positioning, celebrating a figure who spent most of his life serving Hungary’s oppressors while claiming continuity with 1956. Only now is the nation beginning to confront whether such a figure deserves any place in the story of Hungary’s struggle for freedom.

Decades of documented collaboration outweigh a few fleeting revolutionary days. Honoring Nagy insults the memory of Hungarians who resisted communism, endured imprisonment, or died fighting for freedom while he enforced Moscow’s will. Hungarian historical memory must confront this truth. How the nation reckons with it has already shaped its politics and will continue to define its national identity for generations.

Sources:

Csurka István: A nemzet elárulása, Magyar Fórum, 1993

Kuruc.info: Ki volt valójában Nagy Imre? Az NKVD embere a „nemzeti hős" szerepében, 2018

Magyar Jelen: Végre helyére kerül a Vértanúk terének emlékezete, 2018

Magyar Nemzet – Nagy Imre végig kommunista volt

Magyar Nemzet – Orbán Viktor: Nagy Imre újratemetésén vált mindenki számára világossá, hogy vége van a rendszernek

Hungarian Conservative – Imre Nagy, a Controversial Figure of Modern Hungarian History

Mi a munkánkkal háláljuk meg a megtisztelő figyelmüket és támogatásukat. A Magyarjelen.hu (Magyar Jelen) sem a kormánytól, sem a balliberális, nyíltan globalista ellenzéktől nem függ, ezért mindkét oldalról őszintén tud írni, hírt közölni, oknyomozni, igazságot feltárni.

Támogatás